Performance Car February 1992

Ginetta G33 not quick enough for you? Then try the MacDonald Racing's 320BHP Rapide...

It's becoming all too easy to forget what performance motoring is really about. So much emphasis is put on high-tech systems - traction control, anti-lock, four-wheel-steer and the rest, that what matters, which is having fun in something with four wheels and an engine is in danger of being overlooked.

There's a simple way to restore the proper perspective. It's called the Ginetta G33 Rapide.

We are yet to carry out a full road test of the G33, chiefly because Ginetta, a small Scunthorpe based manufacturer, is more interested in delving cars to customers than to the Press. But the few times we have driven the G33 we have developed a real affection for the car. Enough for it to take fourth place in out performance car of the year showdown (December 1991).

High amongst the cars attraction is the 3.9 -ltr Rover V8, who's original 205bhp is sufficient, according to Ginetta to take the car to sixty mph in around 5 seconds and on to 150mph. Quick enough for most people you might think. But not for John MacDonald, of MacDonald racing in Lanchester, Co Durham. He's up rated the engine to produce around 320bhp, and fitted it into a modified G33, dubbed the Rapide.

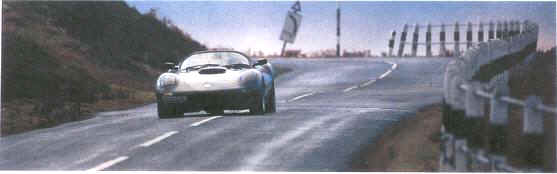

How quick is the Rapide? We had to know the answer. Which is how I came to be sitting in the G33 at the end of a runway on a disused aerodrome in Northumberland.

Now, most of our testing takes place in relatively controlled conditions at the Lotus proving ground at Millbrook near Bedford, but a combination of deadlines and the freezing fog that had enveloped the Midlands ruled that out.

Unfortunately, the aerodrome wasn't perfect, being damp, greasy and bumpy. And the Rapide was quick. Bloody quick. Once I'd mapped out a straightish path through the cowpats and potholes littering the runway, I tried a quick burst of throttle in second gear. A great gob of instantaneous power set the rear wheels spinning wildly. Slotting third, I tried again. The wheels bit, the Rapide surged forwards, but the continual stream of bumps kept unsettling the rear wheels, flicking the tail from side to side. Suddenly the runway seemed very narrow.

To measure third gear acceleration, I took careful aim down the runway and floored the throttle at 30mph. Six seconds later I was travelling at 80mph. By which time the Rapide was bouncing and bucking like a wild west stallion and the rev counter needle had become a blur. The readings were stunning. The Rapide had covered 30-5Omph in 2.5 seconds, 50-70mph in 2.3 and 70-90mph in 2.8. 2 Repeating the process in fourth gear, I gritted my teeth and took it past the ton. The times between 3.4 and 4.1 seconds for every 20mph increment - were remarkable. But the higher speed meant the car arrived at a particularly uneven patch of runway just a bit too quickly. It was too much for the Rapide's miniscule ground clearance. The car grounded with a crack, and when we rolled to a halt a sickly stream of oil began oozing out from beneath it. Goodbye one sump

MACDONALD Racing is everything you'd imagine a small British tuning outfit to be. Tucked away inside a ramshackle collection of buildings is a variety of machinery - mainly traditional, sporting and very British - in varying states of preparation. A glance around the workshop is enough to tell you that this is a business run by enthusiasts for enthusiasts. The ethos of the classic British sporster - small, basic, simply engineered, uncompromising and quick- is revered. Modern electronic wizardry is nowhere to be seen -not because. Ground clearance the depth of an After-Eight mint means sump suffers on bumpy roads MacDonald Racing couldn't cope with it, but because it's an irrelevance to what this brand of motoring is about. H you arrived in a state-of-the-art Japanese supercar the staff here wouldn't give it a second glance. A pre-war Lagonda? Now that would be something else altogether.

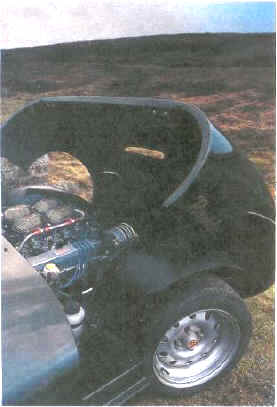

As a Morgan dealer, MacDonald first tuned the Rover V8 for the Plus 8. Given the philosophy of the company, it's no surprise to find that the essence of the modifications to the G33's lump involves ripping out the fuel injection system and bolting on carburetors. Four whopping twin-choke Dellortos. Along with these is a Crane 216 camshaft fitted to gas-flowed heads, and special tubular 4-into-2-into-l exhaust manifolds to help blowout what the Dellortos suck in. The four gleaming air filters squatting on the engine suit the car to a T; there's a classic simplicity to the to the G33's which means you expect to find good old-fashioned carbs on it. It's no coincidence that they're a convenient fit under the G33's buxom bonnet bulge. 'The first time I saw the G33 prototype I knew it would be ideal for our carburetor conversion, explains MacDonald, 'so I badgered Ginetta into making the bulge big enough to fit them.' This gives a hint of MacDonald's relationship with the G33. Looking at the Rapide, you might think that a tuned engine is as far as this conversion goes -only a scattering of conservatively sized 'Rapide' stickers and different wheels distinguish the car from the original.

But since obtaining one of the earliest G33s - the Rapide demonstrator is Chassis No 2 - MacDonald has come up with quite a few improvements. The thing is, without the resources of a major manufacturer, Ginetta has necessarily had to develop its cars during the production process. It's not something the company makes a secret of, and enthusiastic buyers are aware they're not going to receive a car built to Ford- style production consistency. 'But Ginetta do have a reputation for getting things right eventually,' comments MacDonald. 'They're very good at listening to customers and taking on board suggestions.' He wasn't satisfied with the behavior of the front end, which seemed too readily deflected by bumps at speed, so has welded an extra cross member across the front of the chassis to tie down the wheels more securely. Improvements have also been devised for the heater and weather sealing, and a smart tonneau cover has been designed. 'Ginetta still hasn't produced a tonneau,' laments MacDonald.'They don't seem to appreciate how vital one is if you're using one of these every day.'

Every day? Until I visited MacDonald Racing I took it for granted that the G33 was a fun car, designed for sunny summer afternoons and not a vehicle anyone sane would consider using all year round. I soon found out otherwise. The day after the sump-cracking incident, the temperature was hovering just above zero and ominous clouds were gathering overhead. 'Where's the hood?' I enquired innocently. Bemused looks ensued, no doubt accompanied by wry thoughts about soft southerners. 'Hood? Don't know. We've never used it.' To these guys, an open car is an open car, full stop. 'We have a running joke with Morgan,' laughs MacDonald. 'Whenever we go to collect a car from them it's always waiting hood down, ready for us to drive it away whatever the weather.'

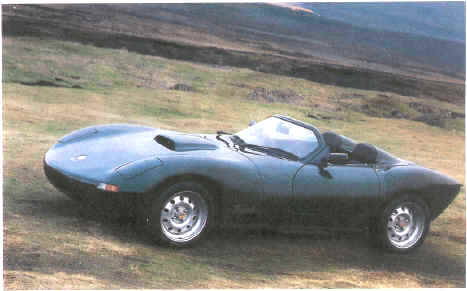

A close inspection of the Rapide doesn't do it too many favours, but this is one of the very first, hand-built cars, remember. Fascia design, panel fits, and many other minor details have been improved subsequently. Even so it's impossible not to appreciate the sensual curves of the glassfibre bodywork, with neat details like flush-fitting door buttons and integrated head rests. The British Racing Green of the demonstrator does it far more justice than some of the more vivid -dare I say kit-car-like - hues available. After my first taste of the Rapide's .Voluptuous styling echoes classics like D-type Jaguar - and so does the performance ferocious performance I approached it warily. Staggeringly quick it may be, but would all that power overwhelm the car? Only one way to find out.

Easing myself into the classic legs- outstretched race driving position, I untangle my feet on the closely packed pedals. Next to sort out are the confusingly labelled switches -most seem to operate a non-existent heated rear screen. There are two switches you really can't ignore -the one that operates the heater, and the one that turns on the fuel pump. MacDonald recommends switching off the latter just before the end of a journey, so not too much petrol is left swilling around the carburetor float chambers. Prod the throttle a couple of times to prime the carbs, turn the key and the engine barks into life. The standard car is loud enough, and this one has an added bite. It sounds ferocious, and spits and coughs intimidatingly until it warms through. It's surprisingly easy to drive. Pedals, steering and gear change are nicely weighted, heavier than the average saloon but not demanding meaty thighs and biceps like some powerful cars. Steering- using a Sierra Cosworth rack- is very direct and precise, so you rarely need to take more than a wristful of the four turns of lock which provide the G33 with a surprisingly tight turning circle. If you like sports cars that need to be revved hard, the Rover V8 in standard form can feel a bit lazy, appealing more as a low-revving slogger than a sporting engine, MacDonald's modifications go a long way to matching it more closely .MacDonald persuaded Ginetta to make bonnet bulge big enough to clear carbs.

MacDonald persuaded Ginetta to make the bonnet bulge big enough to clear the carbs.

There's still plenty of torque at low revs, but as you hold down the throttle power keeps pouring in) building progressively to its 5500rpm peak. By this time you'll have experienced truly vivid acceleration) the sort that turns the scenery into a blur of speed. And because on a greasy surface such a fierce forward impulse is apt to set the tail wagging, you need to keep things carefully in check lest they get a little too exciting.

With its engine set well back in the chassis to avoid nose-heavy handling the Rapide attacks corners with a pleasantly neutral balance. Grip is high, even in the poor road conditions of our test, benefiting from the G33's double wishbone set-up. Understeer is hard to provoke; oversteer with a measured 260bhp at the rear wheels, a little easier.

Special care is needed round tight corners, when over-enthusiastic use of the throttle will send the tail flicking out. Lift off quickly and the Rapide corrects obediently enough, but it all happens a bit too abruptly to feel confident enough to start hurling it into greasy corners. One thing it is hard to adapt to is the lack of ground clearance. Suddenly you realise you're hurtling towards a dip in the road ( braking will only compress the front springs and make matters worse) so all you can do is wait for the crunch. Spare sumps cost £70 each, but it might make sense to order them by the dozen...

Over lesser bumps the Rapide still feels lively, and by 100mph is requiring enough effort to keep it in a straight line to make you feel it's not worth pushing it a lot harder. No matter: unlike most modern supercars, this is a car you don't have to drive at licence-shredding speeds to enjoy, and it's all the better for it.

Brakes, again standard Cosworth- based but non-servo, need a firm application but provide impressive stopping power. Use them hard, and you can feel all four tyres fighting to provide maximum grip.

The G33 is a car that takes motoring back to its basic components. It's a modern interpretation of the classic British roadster- retaining the spirit even if it has lost the walnut and leather. And it's quite open enough to the elements to indulge the hairy- chested enthusiast's masochistic urges -who needs side windows when you can don goggles, a flat cap and a scarf, and let the ice settle on your beard?

With the Rapide, the G33 concept is taken one stage further. This isn't just fun; it's fun with an evil grin. The Rapide's uncompromising ferocity is reminiscent of a pre-war racer. It throws down a challenge the instant it bursts into life. Let off the leash it will hurtle you down the road at a fantastic rate- and it's up to you to tame it. No ABS, no traction control, just a bloody big engine strapped to a spaceframe chassis, and God help you if you can't control it.

The price of the conversion depends on what the customer specifies -the car tested would set you back around £2000 plus VAT on top of the £19,965 for a brand new G33. Whichever way you look at it, this is a lot of extra bhp per pound. Of course the extra power is sheer extravagance; the G33 is easily quick enough -and fun enough -as standard. But if you like your fun to come with a challenge, the Rapide will appeal. If you can tame it, you'll love it.

Quicker than a Lotus Carlton

| Acceleration in 3rd gear | G33 Rapide | Lotus Carlton |

| 30-50 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| 40-60 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| 50-70 | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| 60-80 | 2.3 | 2.8 |

| 70-90 | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| Acceleration in 4th gear | ||

| 30-50 | 3.8 | 4.6 |

| 40-60 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

| 50-70 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| 60-80 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| 70-90 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| 80-100 | 4.1 | 3.8 |